The war against illicit drugs in the United States, Canada, the European Union, and non-EU European countries has cost tens of billions of dollars and has been a colossal failure. Whether we are talking about cocaine, heroin, fentanyl, illegal and legal opioids, or even cannabis, throughout these countries. Interdiction hasn’t worked. Trying to stop growers in the countries where these drugs originate hasn’t worked. Policing of the routes by which these illicit drugs get past border security hasn’t worked.

Grouping all these drugs as illegal has given license to narcotic smuggling gangs who not only reap enormous profits from the trade, but also brutalize populations from where the products originate, and along the entire supply chain.

A Foreign Policy Dispatch published on October 30, 2022, describes how countries of origin for cocaine are striking out on new paths. One of these is Colombia. In his inaugural address, President Gustavo Petro declared that more governments recognize that “the war on drugs has failed.”

That’s why Petro plans reforms to decriminalize the growing of coca leaf from which cocaine is derived. At the same time, he is introducing revisions to the largely failed crop substitution program, legalizing cannabis for non-medical use, and instituting other agrarian reforms to give farmers title to their lands and the license to grow these formerly illegal crops. He has initiated a debate to decriminalize coca leaf. He knows that international treaties governing cocaine will continue to prohibit it, but changing the status in Colombia for coca leaf along with regulating where it is grown and how it is distributed will be the first step in what he suspects will be a decade-long campaign to decriminalize cocaine. In Colombia, there is pushback to the plan from conservative parties and groups, but for the farmers who are seeking a better life for their families and the future, the feeling is positive about the government’s direction.

Joining Colombia are Peru and Bolivia. The October 15th edition of The Economist called for the legalization of cocaine stating that “the costs of prohibition outweigh the benefits.” It describes Petro’s planned reforms in Colombia, and Peru’s President, Pedro Castillo who is following the same path as his Colombian neighbour in decriminalizing coca leaf on the way to eventually making cocaine legal. The Peruvian effort intends to change how coca farmers are treated, from being “narco-terrorists” to becoming “narco farmers” with the product they produce no longer illegal.

The Economist points out that the prohibition of heroin, fentanyl, and cocaine, and federal bans on cannabis are all failed policies. The war on drugs, which began back in Richard Nixon’s presidency, has after a half-century never stopped the flow into the United States. In the last two decades, the cost to the U.S. to try and stop illicit drugs coming from Colombia has amounted to US $10 billion. The illegal growing and manufacturing of cocaine have led to well-armed gangs taking over parts of the country where they actively recruit women and children to be drug mules. In 2020, global production of cocaine hit a record, 1,982 tons, up 11% from the previous year. Back in 1971, very few Americans used cocaine. Today roughly six million are users. And the market has expanded to consumers everywhere.

What feeds the cocaine business is the abundance of coca bushes, the ease and low cost of converting the leaves to cocaine, and the premium gangs get for every kilogram of the drug they sell. Peru today permits 34,000 of its farmers to grow coca on 22,000 hectares of hillside farms. The harvest is purchased by Enaco, a state-owned company.

Bolivia was the original outlier for coca and cocaine. In 2012 it withdrew from the international treaties governing the production and trading of illicit drugs. It decriminalized coca leaf for domestic consumption and today you can buy all kinds of products containing coca leaf extract including toothpaste and coca liquor. Violence around coca growing in Bolivia has declined and communities, not gangs, manage the trade.

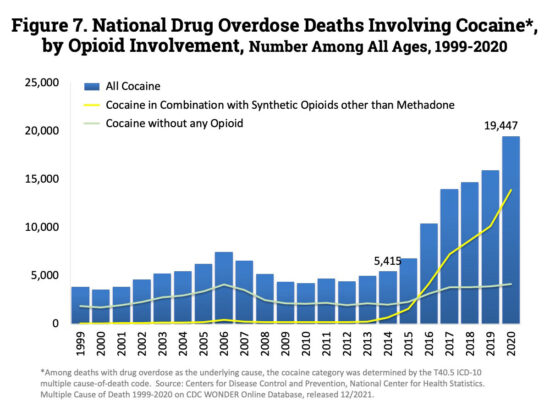

“Legalize cocaine” states The Economist. By doing so “cocaine would be less dangerous.” Like what in the U.S. was once an illegal product, alcohol, the end of “bootlegged” cocaine would mean regulatory standards for labelling and accurate dose levels. Lives would be saved. How many? In 2020, 19,447 Americans died from unregulated cocaine. The death rate has “risen fivefold” states The Economist, in the last decade “mostly because gangs are cutting it with fentanyl, a cheaper and more lethal drug.”

Making cocaine as legal as alcohol and tobacco will lead to more research to study the addictive and potentially beneficial properties of the drug. It will lead to more money being put into addiction programs rather than interdiction. And would you object if the toothpaste you use each morning gave you a mild buzz? How different would that be from the American daily rite of caffeine addiction through the quaffing of a morning cup of jo?