Superconducting quantum interference device magnetometry (SQUID) measures the magnetic properties of materials at the nanoscale. SQUID can measure extremely weak electromagnetic energy fields using two superconductors separated by thin insulating layers which allows a continuous electrical current to flow without additional energy inputs. SQUIDs configured as magnetometers can detect the smallest magnetic fields, even the properties in the brains of birds to understand the internal compass attributes that help them navigate during migration. Or, in this case, a SQUID can be used to map the unexcavated remains of an abandoned city.

When I was in university my field of study was history. My interest was learning more about world empires looking at Rome, Persia, China, early Islam, the Mongols, Ottomans and Russians. I wrote several undergraduate essays on the Mongol Empire and its origins. So when I read an article in the Smithsonian Magazine, that Karakorum, Genghis Khan’s capital established around 1220 AD (or CE based on your dating nomenclature preference), had finally been mapped in detail, I was both curious about how it was done as well as what was discovered.

Karakorum was located in the Orkhon River valley, a pastoral setting suitable for nomadic herders, and a strategic crossroad and water source. As the Mongol Empire was established and began to grow under its first ruler, Genghis Khan, and subsequently his successors, what began as a temporary settlement of yurts (the large round tents that were the homes for the nomadic Mongol tribes) turned into one of stone, masonry and tile with lavish palaces, diplomatic missions, merchant’s homes, markets, artisanal districts, and a permanent population.

Archaeologists from the University of Bonn spent 52 days in 2016-2017, surveying the 465-hectare (approximately 1,150 acres) site. What they found was a city of 1.33 square kilometres (about half a square mile) plus settlement along approaching roads located outside the city walls which extended over 3 kilometres (1.9 miles). SQUID mapping showed that Karakorum was a much larger city than historians had previously thought. Why is that? Because historians assumed that nomadic cultures largely used temporary, not permanent structures such as would be found in the infrastructure of a city of hundreds of buildings and residences.

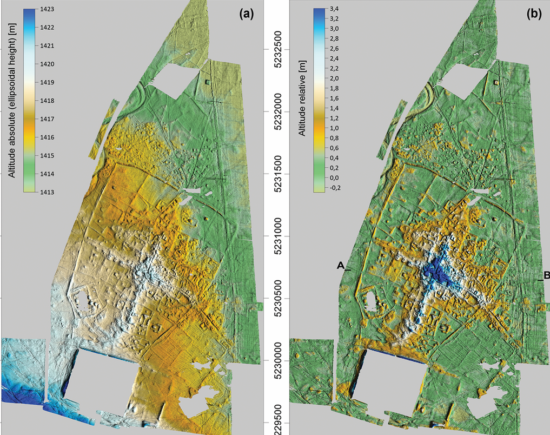

Getting back to the technology used to reveal the lost city, just how does SQUID work? You can see the unit in the image atop this posting. It is battery-driven, and for the Karakorum study included 18 sensors sampling at a frequency of 1000Hz. This produced a high-density data stream amounting to 4 Gigabytes of raw data daily. Data positioning accuracy was so precise, the mapping captured even the tiniest altitude variations of the buildings long-buried on the Eurasian steppe. Erosion had made streets and other topographic features harder to detect but SQUID’s magnetic granularity provides very precise calculations allowing the team to 3D model the city centre showing thousands of its features.

The new Karakorum map reveals a city divided into distinct zones each with different functions and often constructed in different ways. The palatial buildings featured coloured, glazed roof tiles and granite columns. Outside of the palace and central city core and along roads approaching the city’s walls were the remnants of sun-dried mud-brick buildings and homes, appearing in the mapping as square, concave forms.

I went back to my history books. I had written an essay about William of Rubruck, a Franciscan missionary who visited the city in 1254 AD. His description noted four gates aligned north, south, east and west, and streets coming from numerous directions outside the walls to deliver goods for trade including a lot of livestock which was no surprise. Rubruck noted that the southern gate stood closest to the imperial palace.

A Persian historian of the 13th century, Ata-Malik Juvayni, described the city similarly and added more details. He noted that the palace itself had four gates each with a different purpose: one for the Khan, another for his kin and children, a third for the princesses of the realm, and the fourth for petitioners and city dwellers. SQUID mapping largely confirms the artifacts as described.

Karakorum was an implanted city. It arose from nothing and then vanished in short order as the Mongol Empire fragmented into smaller entities and eventually was assimilated by the populations the nomads conquered. The Khanate of the Golden Horde in western Asia eventually succumbed to Russia. The Ilkhanate of Persia and the Fertile Crescent reverted to a series of local Islamic dynasties. And the eastern fragment, by far the largest and richest became the Yuan Dynasty of China, ruled by Genghis’ grandson, Kublai. It is the court of Kublai Khan whose story became known to Europeans as recounted by Marco Polo.

Karakorum’s return to the steppes happened a little over a hundred years after its founding. Within a few centuries, the land was once again pasture, as it was before Genghis Khan decided to make it the centre of the largest empire the world had and probably will ever see.

As for SQUID, besides mapping lost cities to reveal them, it is proving to be an exciting technology with important application for numerous fields of study. Because it is more sensitive than any other magnetic detection technology its use in gradiometry, the ability to measure gravity and magnetic fields has application for astronomy, biology, geology, and medicine.

But for me, who studied the history of empires such as the Mongols, SQUID has given me a picture of a place and time that always was wrapped in mystery.