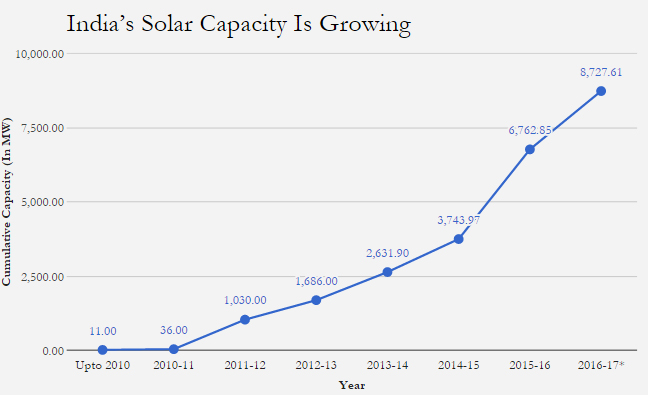

May 30, 2017 – In the last week experts on China’s population have questioned whether the government’s population figures are accurate. These experts feel the numbers are far too high and that means India is now the most populous country on the planet. Not only the most populous, it is also the economy that is growing at a clip only second to China with demand for energy projects dramatically on the rise.

Under India’s Minister of Energy, Piyush Goyal, the country is pushing ahead with building energy capacity. What type is the critical issue? If based on coal it means India will contribute more carbon emissions to the Earth’s atmosphere. If based on renewable energy, it means capacity growth will not contribute to rising CO2 levels.

A new 10-year energy blueprint published at the end of 2016 suggests that the latter, rather than the former, will be India’s plan. No new coal-fired thermal plants are to be built even though Indian energy companies have many on the drawing board and in planning phase as well as investments in Australian coal mines which all seem counterintuitive. So is the coal investment a reflection of the country’s existing thermal power plant capacity requirements, or a hedging of bets against the success of renewable energy?

Part of the problem India faces is the lack of capital to grow its renewable energy capacity. Goyal is on a mission to attract capital investment for domestic renewable energy projects with rural electrification a primary focus. The country has created the Remote Village Electrification Programme (RVEP) to provide renewable energy to un-electrified villages. So far renewable projects have brought electricity to over 11,000 villages and hamlets. But renewable investment is lagging because the government at both the national and state levels has insufficient capital to speed up these types of energy projects.

In the last year Softbank, the Japanese company, along with Taiwan’s Foxconn, and India’s Bharti Enterprises have committed $20 billion U.S. to Indian solar energy projects. And the French state-owned energy company, EDF, is also making a $2 billion investment in wind and solar. The Tata conglomerate, the owner of Jaguar and Land Rover, has committed to generating 40% of its domestic energy requirements from renewables by 2025.

Tim Buckley, of the Institue for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, points out that India’s transition to renewables is transformationally disruptive. He comments, “India is moving beyond fossil fuels at a pace scarcely imagined only two years ago…..Goyal has put forward an energy plan that is commercially viable and commercially justified without subsidies, so you have big global corporations and utilities committing to it.”

By 2027 India intends to generate 275 Gigawatts from renewable energy, 72 Gigawatts from hydroelectricity, and 15 Gigawatts from nuclear. In addition, another 100 Gigawatts will come from “other zero emission” sources. That compares to 50 Gigawatts in coal thermal power projects currently on the books that Buckley believes will be “largely stranded.”

Where India continues to struggle is getting the population on side through the adoption of renewable energy initiatives such as solar rooftops in its urban centers. Despite policies from the Ministry that provide subsidies of 30% for installation of solar, adoption in cities like Chennai and Mumbai, is described as dismal to date.

With energy generation key to India’s goal to reduce poverty, particularly in its rural areas, the country recognizes that its current energy mix produces 61% of its greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs). The only way, therefore, for India to meet its Paris GHG commitments is to make a rapid conversion to renewable and other low or zero-emission energy sources. Ultimately, all of us on the planet will be the beneficiaries of Piyush Goyal’s efforts.