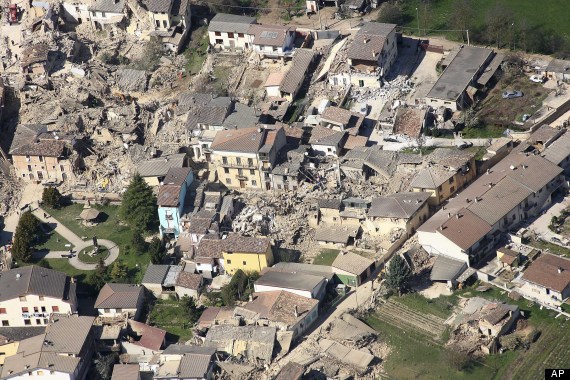

Seven geo-scientists have been found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison by an Italian court because the scientists failed to predict a 6.3 magnitude earthquake in 2009. That earth-moving event caused the death of 308 people in and around the city of L’Aquila. The convicted scientists served as members of a risk assessment committee providing advice to the government on potential natural disasters. In this witch hunt conducted by the Italian justice system the scientists were accused of improperly assessing the risk and likelihood of a major earthquake after a series of tremors were felt in the region around L’Aquila.

Predicting earthquakes is predicting the unpredictable. Lifetaking tremors can be sudden or follow relatively benign ones that go on for days. And although scientists can track earthquake waves when they happen no human has yet to show the ability that some animals are said to have, to feel an earthquake and behave bizarrely before it strikes. If scientists had this skill then Fukushima wouldn’t have happened and no Japanese court has hauled in seismologists to accuse them of manslaughter for the 2011 undersea earthquake that resulted in the devastating tsunami that struck Japan. Nor have any scientists been tried for not predicting the 2004 earthquake and tsunami in the Indian Ocean that killed almost a quarter million.

So what has gone wrong in Italy?

Italy has a National Commission for Prediction and Prevention of Major Risks. It is that committee that was put on trial. In late March of 2009 the committee met to assess a series of minor earthquakes around L’Aquila. The city had experienced devastating earthquakes in the past such as the one that struck in 1703. But the committee in its judgment at the March meeting felt it was unlikely that an earthquake similar to the one in 1703 was going to occur even though it couldn’t be completely ruled out. Six days after providing these conclusions to the Italian government the earthquake struck. The court’s reasoning was simple. If the scientists had predicted an earthquake and evacuated the town there would be little loss of life. But the scientists didn’t and therefore they were to blame.

Animals and Predicting Earthquakes

You see the scientists with all their theory and technology couldn’t do what Italy’s common toads could – predict a coming earthquake. just prior to the earthquake Rachel Grant, a doctoral student in Life Sciences at London’s Open University, was studying the breeding habits of a toad population at a location not too far from L’Aquila. The common toads in Italy mate and reproduce once a year. This involves a significant annual migration that has them gather at a common breeding ground. Five days before the earthquake, Grant noted that the toad population vanished dramatically going from 100 down to zero in two days. The breeding ground was 74 kilometers (46 miles) from L’Aquila. In her study published in the Journal of Zoology in 2010 she concludes there is a correlation between the toads’ disappearance and the onset of the earthquake.

Humans and Earthquake Prediction

Predicting earthquakes is more art than science except if you are a toad. Non-toad geophysicists, seismologists and geoscientists have learned a significant amount about what lies beneath our feet. From simple seismographs dating back 2,000 years to the past century when the science of plate tectonics was discovered, scientists have been able to map those areas of the world most prone to earthquakes and volcanic activity. Italy and the Mediterranean Sea basin are in one of those geological active zones where earthquakes happen and volcanoes, from time to time, erupt. But predicting when these events happen remains as much a mystery today as they were two thousand years ago. All scientists have to go on is evidence gathered from the historic data and from sensors that record current seismic activity. At best they can speculate on the likelihood of an earthquake occurring in a particular region – in short, giving odds.

Short of adding seer, psychic or visionary to their curriculum vitae, the scientists in Italy that served on the Commission had little to go on that would have foreshadowed what happened in L’Aquila. They might have been able to state that based on past observations of earthquake activity that there was a probability of an earthquake at some point in the foreseeable future. And this they did. But as to the point in time or the severity, the Italian scientists, and all scientists who study earthquakes, had no prescient ability to provide an accurate forecast.

So how will this all end?

We can only hope that sanity eventually prevails in the Italian courts when the scientists appeal the verdict. In the 21st century no judicial system should be convicting anyone because they couldn’t predict when an earthquake would occur. This is outright ignorance and stupidity piled upon a tragedy in which 308 lives were lost. Blaming the scientists is misdirected vengeance. Why don’t the Italians just march them up the slopes of Etna or Vesuvius and drop them in the caldera? It would be the same kind of justice as what the courts have served.

I couldn’t agree with you more, Len. I’ve read that there’s no incarceration before an appeal so let’s hope better judgment prevails at that hearing.

A potentially interesting item could be to examine the mandate of the National Commission for Prediction and Prevention of Major Risks. Perhaps it was its loose wording that provided the foundation for the suit (purely speculation). If so, it begs the question of what the mandate of such organizations should be, but it’s obvious that one item should be public education on reasonable expectations.