November 1, 2018 – On a globe or map of the world the lines of latitude, known as the Tropic of Cancer, and Capricorn, mark the limits of Earth’s axial tilt as it makes its yearly orbit around the Sun. We associate these lines with climate as well. Above the 23rd parallel north or south and we are into more temperate climates. Inside the 46-degree band that encircles the planet lies the tropics.

Or so it would seem. But climate reality reveals something different. The real tropics aren’t defined by these two lines of latitude. You have to get much closer to the equator before things get truly tropical. This is an area defined by global atmospheric circulation surrounding the equator. The heat generated within this narrower band, however, exerts a much greater influence that goes beyond the 23rd parallels, in fact as high as the 30th parallel.

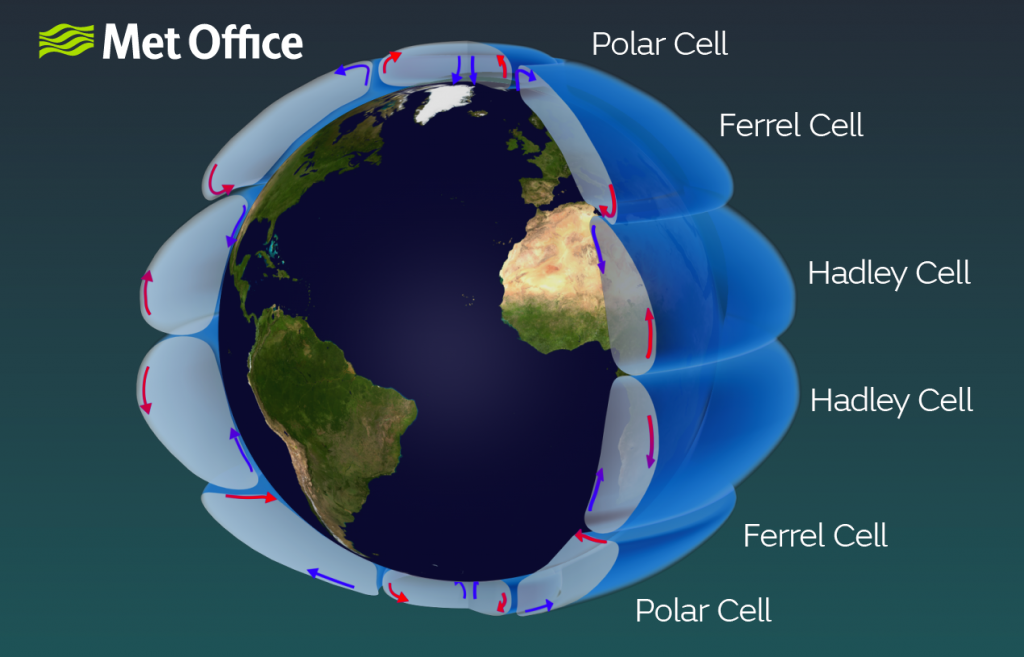

We call the tropical air circulation pattern that transcends the equator, Hadley cells, named after an English meteorologist, George Hadley. One of the Hadley Cells conveys hot tropical air to the north while the other conveys it to the south. The Hadley cells are two of the atmosphere’s six conveyor belts. Going poleward away from the equator lie the Ferrel cells which circulate air from the edge of the Hadley cells to an area between 60 and 70 degrees of latitude. And then further poleward are the Polar cells which begin between 60 and 70 degrees latitude and go to the poles. These six global cells create the weather we all talk about every day. The boundary between the Ferrel and Polar Cells is where we find the Jet Stream, that conveyor belt that brings warm air into northern latitudes or channels a polar vortex into more southerly climes.

So that’s the way the atmospheric circulatory system is constructed. The lines of separation have been pretty much the same throughout our recording of global climate, that is, until recently. Humans have been accurately recording climate records for about a century-and-a-half, almost equal in time to the rise of the Industrial Revolution. And for much of the first century of record keeping not much changed. But that’s not the case anymore.

In a paper entitled, Re-examining tropical expansion, appearing in Nature Climate Change, authors Paul Staten, Jian Lu, Kevin Grise, Sean Davis, and Thomas Birner, describe the widening of the Hadley cells by approximately 0.2 to 0.3 degrees of latitude per decade since 1979. The reasons given for the shift include greater amounts of carbon soot from pollution sources in Asia, increasing amounts of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen dioxide, and other greenhouse gases during this period, and changes in ocean surface temperatures.

What does this mean for us? The shifting of the edge of the Hadley cells directly impacts climate zones, and weather over the lower mid-latitudes of the planet where much of human population lives. The authors of the study believe the shifting is contributing to such observable events as the growth of the Sahara and Kalahari Deserts in Africa, and that it is also contributing to prolonged droughts in some parts of the planet, such as the Mediterranean basin, and the Southwestern United States down into Central America. That so-called caravan of migrants coming from Central America to the Texas border is, in fact, a movement of climate refugees forced from their home countries by persistent drought, imperiled economies, and rising crime. And the shift in the Hadley cells is altering biomes with normally tropical insects spreading into previously considered temperate climate zones bringing along with them a number of serious diseases including malaria, dengue fever, West Nile virus, Zika, chikungunya, and others.

The migration of the edge of the Hadley Cells is also affecting the neighbouring Ferrel cells which are also being shifted poleward as a result. That means smaller Polar cells and changes to air circulation patterns over places like northern Canada and Alaska contributing to an observable change in the permafrost line which has moved by almost 130 kilometers (80 miles) to the north over the last 50 years. Similar changes are happening in Central Siberia where the permafrost line is moving north. And in Siberia, it is causing unexpected outbreaks of diseases like anthrax as frozen animals in the permafrost thaw out releasing deadly pathogens.

If the migration of the Hadley cells continues it will have profound impacts on the growing zones where much of the food we eat gets produced. That’s food for thought. So what can humans do about it? This latest research tells us the changes to the Hadley Cells is largely attributed to our human impact on the atmosphere from ozone holes to greenhouse gas emissions. That means we know what has to be done to stop and reverse the expansion.

In Canada, we have implemented a price on carbon pollution in the form of a consumption levy put on pollution sources. Some provinces in the country have decided to fight this national policy which doesn’t help us get to where we need to go.

South of the border in the United States, the federal government has chosen not to do anything, and in fact, in recent weeks has attempted to lower pollution standards for vehicles, has tried to revive coal mining and coal-fired power plants, and is opening up the Arctic Ocean to offshore oil exploration. Let’s hope a mid-course correction can begin in the United States after the 2018 mid-term elections this coming week. Because without the United States participating in combating climate change, Hadley cell migration and other global changes to the climate will eventually place many American and other lives at risk to disruptive weather events spawned by anthropogenically caused changes to the planet’s atmospheric circulation.