July 31, 2015 – Today United States crude production includes 9% contribution from Canadian oil sands. By 2020 that number is expected to climb to 14%. This estimate is independent of whether the northern leg of the Keystone XL pipeline gets built or not. So the United States has much invested in Canadian oil sands production and as a result the U.S. Department of Energy has been tasked with studying its carbon impact. The work done by the Argonne National Laboratory, Stanford University and University of California at Davis when published in June of this year describes the environmental impact of fuels made from all domestic and imported sources in the United States and within this Canadian oil sands. The analytical tool used by the study has been given the acronym GREET which stands for Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Transportation.

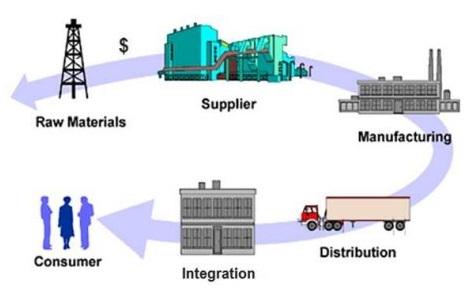

GREET does a life cycle analysis of fuels and their use from “well to wheel.” As in the image below, that means from the point of extraction to when it gets burned to supply energy to your car. The image below roughly illustrates what that means.

Using GREET and data from 27 Canadian oil sands production facilities, the Argonne-led study found full life cycle energy emissions from oil sands derived crude to be 20% greater than conventional oil from U.S. domestic sources. The difference is attributed to the energy required by oil sands producers to extract and refine their product. The study also looks at methane and carbon emissions, the former from tailing pond evaporation and the latter from the energy expended by machinery to remove the overburden in oil sands extraction processes.

The two common methods to harvest oil sands, one involving surface mining (see image below), and the other, steam injection, are very energy intensive. Depending on which method of extraction the Argonne Laboratory was able to assign a carbon intensity value for the finished gasoline product between 8 and 24% higher than conventional crude sources.

Although this is the first fuel life cycle analysis providing critical detail on the carbon intensity of oil sands crude, what it doesn’t assess is the role U.S. refiners play in that measure of intensity. For example, do Texas refineries that process heavy crude from Venezuela today have the technology in place to minimize carbon emissions if oil sands crude were to be substituted?

One thing for sure, oil sands operators, in the current economic climate of depressed crude prices, will be inhibited from making significant investments in further reducing carbon intensity per unit of production which is the current Canadian measure for carbon reduction commitment from this sector. Many oil sands operators are mothballing projects that use steam injection, far less carbon intensive, and others are reducing the volume of product output from existing operations.

Meanwhile the Keystone XL pipeline remains a hot political potato in the United States. Just a few days ago U.S. Senator John Hoeven predicted that President Obama will nix the building of the northern segment of the pipeline. Senator Hoeven who is an advocate for the pipeline and a Republican describes the decision as political, not environmental, and ascribes the nuclear deal with Iran as the reason. Meanwhile the Democratic hopeful, Hillary Clinton, while on the stump in places like New Hampshire and Iowa, has avoided addressing Keystone XL and when pressed by reporters stated, “if it’s undecided [approval of the pipeline] when I become president, I will answer your question.” Bernie Sanders, one of the other Democratic hopefuls has made his position clear. He is opposed to building Keystone XL stating, “it is hard for me to understand how one can be concerned about climate change but not vigorously oppose the Keystone pipeline.”

If Senator Hoeven’s prediction proves accurate, President Obama will have in hand the Argonne National Laboratory study and his target reductions for carbon emissions as more than enough justification for the decision not to proceed with Keystone XL. But will it make a difference? If crude prices rebound then expect oil sands product to flow south to U.S. refiners by other means. So unless oil sands producers significantly reduce intensity per unit overall the carbon contribution from their product as volumes ramp up will increase net emissions.