November 21, 2014 – When I was a young man we lived two blocks from a freshwater-fed pond by the name of Tillplain. Today it is gone, covered and built upon. That’s where the high school I graduated from currently stands. But that pond unlocked the mysteries of life for me and so I remember it fondly.

I would gather my investigational tools, sampling bottles, nets and waders and head off in search of tadpoles, dragonfly nymphs and all kinds of other aquatic life. With bottles filled I would return home and populate my freshwater aquariums so that I could study my finds.

Amon the specimens I collected were daphnia, the common water flea. It was fascinating under magnification to watch them as they swam. Eventually my tadpoles turned into frogs and my dragonfly nymphs emerged to fly away. I think the neighbours must have wondered often what kind of menagerie was going to hatch next. It amazes me to this day that my parents tolerated all of this.

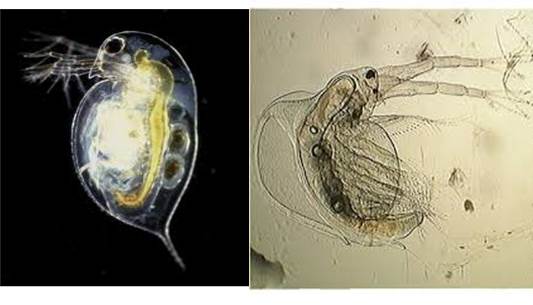

But what brought back these memories was an article that appeared in a local paper a couple of days ago entitled, “Acid rain leaves ‘jellification’ in Muskoka, Haliburton lakes.” The author, Kate Allen, talked about the disappearing of daphnia from lakes in Ontario, and the reasons hypothesized by freshwater biologists for this phenomenon. It also talked about what was replacing daphnia in abundance because of their decline, a spcies called holopedium. That’s daphnia on the left and holopedium on the right in the picture below.

They don’t look significantly different but they are. Daphnia are an important part of the food chain of freshwater lakes. They are symptomatic of healthy, nutrient-rich freshwater systems. And they are food for a chain of water creatures from salamanders and newts to small fish. And daphnia require calcium rich water to ensure their health.

But declining calcium is the unforeseen consequence I refer to in the title of this posting. It appears that it has been leached from the lakes accelerated by the legacy of acid rain and forestry. Acid rain was an environmental crisis fought in the 1970s and 80s by environmentalists who were able to get legislation passed for the installation of pollution abatement technology to remove sulphur from smokestack effluent. That sulphur was causing sulphuric acid fallout as it combined with water vapour in the atmosphere. As the acidic rain fell on lakes and rivers it lowered pH levels and leached out the calcium. The cutting of timber near freshwater lakes also reduces calcium levels in water as the byproducts of cutting wash into rivers and lakes lowering pH levels.

And although forestry practices remain the post-acid rain era was supposed to restore lakes to normal pH balance. But alas, not calcium levels and the poor daphnia with depleted stores are being pushed out by holopedium, a competitor who appears to be less fussy about low levels of the mineral in freshwater. Apparently holopedium’s carapace is thinner than daphnia and not as susceptible to low calcium in the freshwater environment. Hence holopedium is on the increase.

The evidence gathered by freshwater biologists and published in The Royal Society Proceedings B is entitled “The jellification of north temperate lakes.” The authors of the study note the phenomenon of daphnia decline and holopedium increase observed in aquatic ecosystems from eastern North America to northern Europe. Lakes once dominated by daphnia are now seeing the growth of holopedium and this is impacting other wildlife. It turns out fish and freshwater life that fed on daphnia are not too keen about holopedium as a substitute. For those who do eat the holopedium it is proving to be a poor nutritional substitute because of its lower calcium levels. So as holopedium populations grow, native wildlife higher in the food chain is compromised,, an unforeseen legacy of acid rain.

And why do the scientists refer to this as the jellifcation of the lakes? That’s because a handful of holopedium is very jelly-like. The picture below was taken by Ron Ingram of the Ontario Ministry of the Environment. That’s holopedium in hand with the look and feel of jelly.

[…] Daphnia, once a dominant crustacean in eastern North American and northern European ponds and lakes is in decline impacting food chain. […]