January 14, 2019 – The kerfuffle south of the Canada-U.S. border that has led to a partial shutdown of the federal government is all about the President wanting to fund a physical border wall. His political ascendancy has been all about putting a barrier between the U.S. and Mexico based on a premise that America’s southern neighbour has little control over its citizens or migrants from other parts of Central and South America wanting to crash the border. There remains little evidence to support the President’s position, but meanwhile, he holds the federal government as a hostage to get Congress to accept his premise and put money towards the project.

Physical walls have an interesting history. The first walled cities date back thousands of years. The notion of building ramparts to create defensible positions is intrinsic to human nature as we try to protect ourselves from strangers who may want to physically harm us. Physical walls work in the short-term, but not over time. Technological innovations eventually find ways to breach the walls.

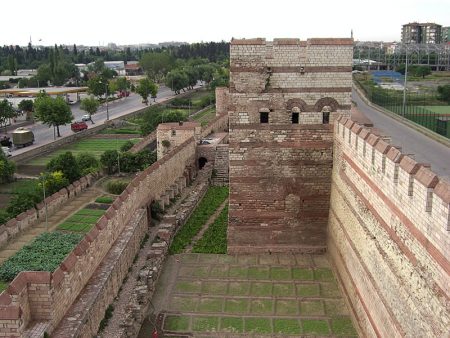

Take for example the walls of Constantinople, the once capital of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. Those walls erected over hundreds of years and rebuilt and extended many time kept tribes migrating across the Danube and through the Balkan as well invaders from Asia Minor at bay from the 5th to the 15th century. Constantinople’s fall in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade was an inside job. No walls could have stopped the Latin kingdom forces invited in as mercenaries. So it wasn’t until 1453 when Ottoman cannon fire breached the walls, a relatively new technology, that the last vestige of Rome’s imperial legacy succumbed.

The Romans in first century Britain built Hadrian’s Wall to keep the Celts north of it from raiding the imperial province of Britannia. But in the fifth and sixth century, the wall turned out to be useless in stopping raids and eventually migration by sea from Anglo-Saxon tribes, part of a mass movement of Germanic peoples eventually overwhelmed the entire western half of the Roman world.

And then there is China’s Great Wall, built over a five-century period to keep tribes living in Mongolia and Central Asia from raiding the various dynasties of the Middle Kingdom. How effective was the wall? It didn’t keep anybody out as Chinese rulers were repeatedly supplanted by invaders from Central Asia, some of them permanently establishing new dynasties. Successful breaches of the Great Wall included the Xiongnu (known in the west as the Huns), back in the fifth century. Later came the Mongols in the 13th century who established dynastic rule over all of China for more than a hundred years.

So it seems that physical walls designed to stop invasions are seriously limited even though they make for impressive engineering projects. Maybe that’s why President Trump wants a wall since his background is in building mega projects, big buildings with his name prominently displayed. So why not a Trump wall?

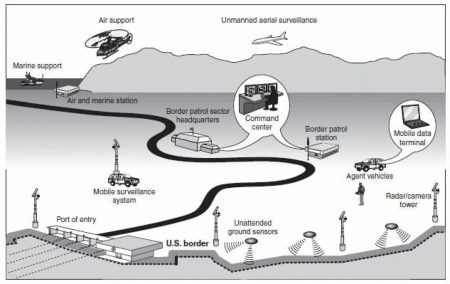

But what about a non-physical wall that uses electronic and digital technology in its stead? This type of wall would be invisible to the eye but would act as a virtual presence capable of stopping illegal entries and smuggling. In Arizona near the town of Sasabe, such a wall was proposed and built in the 2000s to create a virtual border fence. Part of the Secure Border Initiative, Boeing deployed a combination of fencing, vehicle barriers, radar, satellite, ground and underground sensors, and high-powered cameras with a 16-kilometer visual range mounted on towers. Many parts of this Boeing virtual wall were invisible to anyone crossing them with fencing being used to demarcate only areas deemed to be natural crossing points. The virtual fence project which started out with a budget of $70 million USD, ended up eventually costing $1 billion for just 45-kilometers of “wall.” Boeing had hoped the demonstration would lead to implementation along both the Mexican and Canadian borders. But there were far too many glitches, complaints from local residents, and significant cost overruns. For example, the area chosen for the test virtual wall turned out to be a migratory route for lots of animals who kept triggering the sensors to produce false alarms. And then the virtual wall straddled an area where people on both sides of the border frequently crossed to work and socialize. And then radar interfered with foraging bats. Conservationists were alarmed at the potential impact the virtual wall would have on rare species in the area such as the ocelot.

In the end, the project was canned. But should something like it be reconsidered in the face of the current U.S. executive in Washington hellbent on building a physical wall that is estimated to end up costing upwards of $70 billion USD or more? Wouldn’t a better iteration of a virtual wall prove more cost-effective? It wouldn’t look as impressive, wouldn’t make for great photo-ops. But with the bugs worked out, and maybe a little artificial intelligence technology, it could prove to be far more effective than concrete or steel because a virtual wall would give U.S. border agents a digitally-enhanced unencumbered view of what’s going on right in front of them. Then they could discern whether border crossers, deemed by the administration to be rapists, murderers, and drug lords, turned out to be only families with children in desperate straits fleeing failed countries and seeking a safe haven and New World to which they can contribute as productive members of American society.

How is the plight of Central American families fleeing climate change, drought, and failed states, much different from the Irish who fled their homeland in the 19th century because of famine and the lack of action through failed policy by the British government to help? The America of that time didn’t close down its borders to the millions who came seeking shelter. The only difference is the Irish were white.