September 12, 2018 – Naming rights may soon be coming to space with NASA’s Jim Bridenstine, the non-scientist, non-engineer, politically appointed administrator, directing his agency staff to license rockets and space mission in the same way names are added to football, hockey, soccer, and baseball stadiums.

This is a departure from naming conventions used by NASA in the past. Think Dawn, New Horizons, Curiosity, Phoenix, Messenger, Voyager, Viking, Tranquility Base, and the Eagle has landed, and you conjure up images of the science, engineering, and wonder associated with the agency’s past missions. But now Bridenstine believes that cereal box advertising should appear on the side of NASA rockets, and corporate names should accompany space missions.

In a recent meeting of NASA’s Advisory Council, Bridenstine made this point stating that he felt a move like this would make space activities more relevant to the public and would serve as a separate source of revenue to apply to agency activities and missions. So we could have instead of Apollo 11 the Stella Artois 11 lunar mission.

Arguing that naming rights and the revenue derived from this practice would make space activity more relevant to the public is absurd. Think about how transfixed are world was in 1969 when NASA landed two astronauts on the Moon.

And remember how headlines about New Horizons appeared on the front page of newspapers everywhere when that robotic spacecraft rendezvoused with Pluto sending back its amazing images.

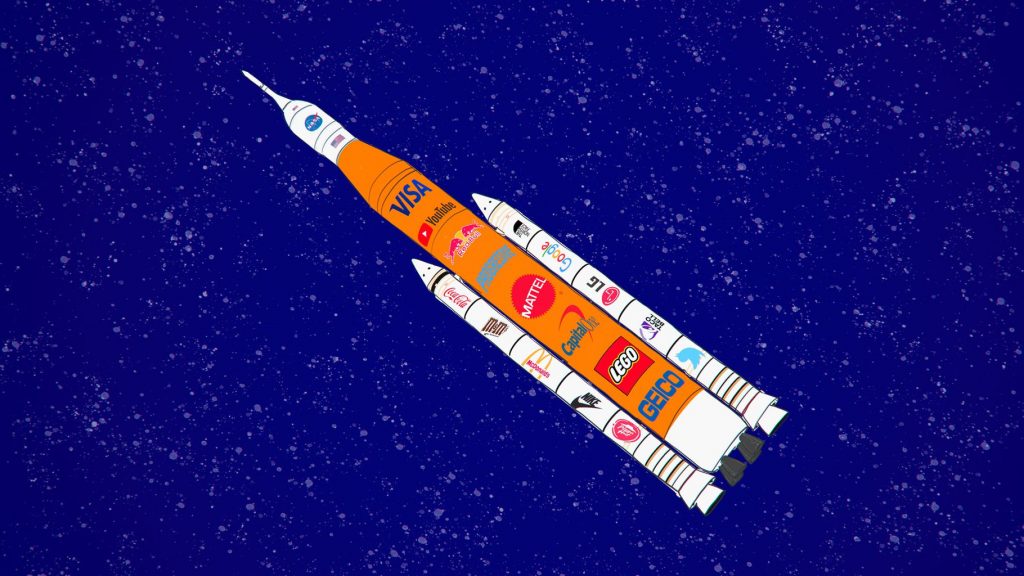

Space exploration and space missions have never been mundane. They are not programs to be seeded with logos carefully placed in the background of video broadcasts. And they don’t need to be painted on the sides of agency rockets that until now have remained spare of logos other than those of NASA itself.

Of course, today we have SpaceX and other commercial space companies such as Boeing, Bigelow, and Blue Origin, who are all now part of the agency’s mixed program that supports a growing non-government, for-profit industry.

SpaceX prominently displays its name on the side of every Falcon 9 and Dragon capsule launched. Boeing’s Starliner will certainly do the same. But so far, neither Boeing or SpaceX are selling naming rights to third parties to cover research and development or launch costs, or funding for further corporate activities. It may happen in the future as commercial operators, but should it happen with NASA?

NASA is a U.S. government agency with an international presence and worldwide reputation. Astronauts may pop a few zero-gravity floating M&Ms when in orbit on the International Space Station (ISS), or may use a cappuccino maker sent to them for their use, but the branding associated with these Earth-comforts are not overtly displayed. Those M&Ms aren’t what makes activity on the ISS memorable, and Bridenstine’s argument that the public will be more motivated to watch if commercial logos and products appear on NASA missions misses the point. It is the zero gravity phenomenon that is transfixing, not whether the M&Ms are plain or peanut. If anything I think Bridenstine’s suggestion of commercial branding may make NASA seem far more mundane.

Imagine if the naming practice follows that of stadiums which regularly get renamed when term-limited licensing agreements expire.

Two examples: recently the Air Canada Centre in downtown Toronto was renamed Scotiabank Arena. It will bear that name for the next 20 years until someone else comes along with cash to put their brand on the facility.

And there is Toronto’s SkyDome, home to the Blue Jays, which got renamed the Rogers Centre when that company bought the baseball franchise. Should the franchise be sold in the future to another company it is likely to be renamed again.

So will we see in the near future a Coors’ Light Lunar or Mars Colony? And after 20 years will NASA sell naming rights to another corporation who will then mount a mission to the Moon or Mars to change the signage? And will the rocket they use be emblazoned with corporate logos?

Imagine spacesuits festooned with advertising patches similar to what we see on sports teams’ uniforms.

Or the Nike swish becoming NASA’s secondary brand.

Having said this it should be noted that the precedent has already been set by the Russians who painted the Pizza Hut logo on a rocket back in 2001 in a resupply mission to ISS. Pizza Hut paid Russia $1 million for the naming rights.

But NASA should feel free to sell licensing rights of its own brand to corporations to make some extra money. For example, to inspire future engineers and rocket scientists I see no reason why NASA can’t lend its name to scientific and engineering toys and models. I am sure LEGO, Mattel, and others would be happy to pay for the NASA emblem.

But creating the LEGO or Mattel Lunar Colony should not be in the cards.