November 11, 2017 – In downtown Toronto, one lonely wind turbine generating 750 kilowatts at full speed sits near the water’s edge of Lake Ontario. It is an orphan, and more often than not in the last few years has sat immobile. It is not where the industry is today and is certainly not where wind power is going.

And exactly where is wind power going these days?

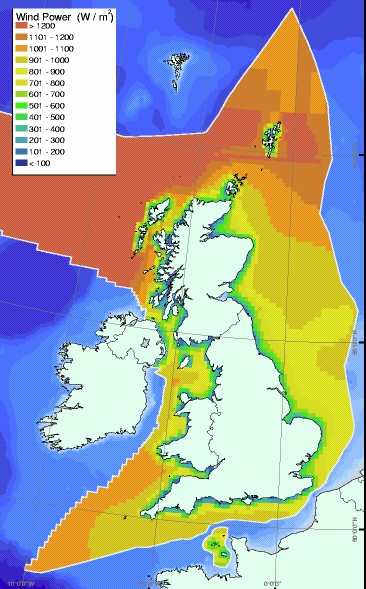

To see how wind power can become a reliable and primary energy producer go to the United Kingdom where it is being implemented on a massive scale. Known as the windiest country in Europe, the UK currently operates 8,000 wind turbines generating electricity to 11 million homes. Plans call for additional growth until wind can meet 40% of the country’s energy needs, an increase from the current 11.5%. For the UK wind is the primary choice for replacing coal-fired power, and the proximity of the North Sea provides the country with as close to a wind paradise as possible. That’s why today wind farms are being placed hundreds of kilometers off the UK coastline, and the turbines being erected are massively bigger than anything seen previously on land or at sea.

To give you a comparison, in Ontario where the province is bordered by four of the five Great Lakes, there are no wind turbines over water. NIMBY (not-in-my-backyard) resistance is the likely reason that such projects have not made it beyond proposals. But instead, the province, with detailed maps of wind capacity over land, has tendered contracts to numerous suppliers who have built thousands of turbines which can be seen throughout much of Southwestern Ontario where large expanses of relatively flat terrain provide consistent wind speeds. In a recent driving trip that took my family to this part of the province, the sight of these windmilling colossi was indeed impressive. But nothing we witnessed compares to what the UK is building.

An average wind turbine in Ontario stands between 85 and 115 meters (280 to 380 feet) in height. Each turbine blade, made of fiberglass or carbon fiber, stretches 45 meters (nearly 150 feet) in length. And with each rotation a blad, can exceed 160 meters (525 feet) in height at the topmost point of its sweep. Such turbines generate 2.5 Megawatt of electricity per rotation individually. When operating at full capacity (the wind needs to continuously blow), each can generate in excess of 20,000 Megawatt hours per year. But if the wind blows only half the time, the yield is reduced to 10,000 Megawatt hours annually.

In the UK, however, the latest wind turbines stand 195 meters in height, each featuring massively long blades and yielding 8 Megawatts of power per single rotation. That means just one of these operating at 100% capacity can generate more than 65,000 Megawatt hours per year. And because they are on the water, wind reliability is very high. That means near full capacity year round.

There is a drawback to placing wind turbines at sea. What happens when one breaks? A turbine that suffers a mechanical failure when at sea requires sending a workboat and repair team, working in less than ideal conditions. A solution that can reduce the cost and risk of over water wind turbine failures, is to build them to float. Then if a mechanical failure occurs, you can tow it to shore for repairs.

In the UK, the world’s first floating wind turbine farm opened last month. Located 24 kilometers (15 miles) off the Scottish North Sea coast, it contains five 253 meter-tall (830 feet) towers with 78 meters (256 feet) of their length beneath the sea’s surface. Each turbine is tethered by massive chains to the seabed. And each has the capacity to generate 6 Megawatts per rotation. There are plans to add more of these floating behemoths not only off Scotland’s North Sea coastline but also in the neighbouring Irish Sea to the west where some of the largest anchored wind turbines lie offshore near Liverpool. A field of 32 of these behemoths generates 8 Megawatts each per single rotation, enough power to keep a house heated and lit for 29 hours.

So size does matter and as we can see, so does location. If the UK experience proves anything, wind can be a significant contributor in the mix to lower the planet’s collective carbon footprint while providing the energy we all cannot live without.