June 9 , 2016 – Altering the genetic structure of organisms is a power not to be taken lightly. But that is exactly what is possible today through advances in genomics. Because of tools like CRISPR/Cas9 we can reinvent an animal and spread new genetic traits through a entire wild population for good or bad. In the case of the Zika-carrying Aedes aegypti mosquito, the good would be the suppression and elimination of the entire population.

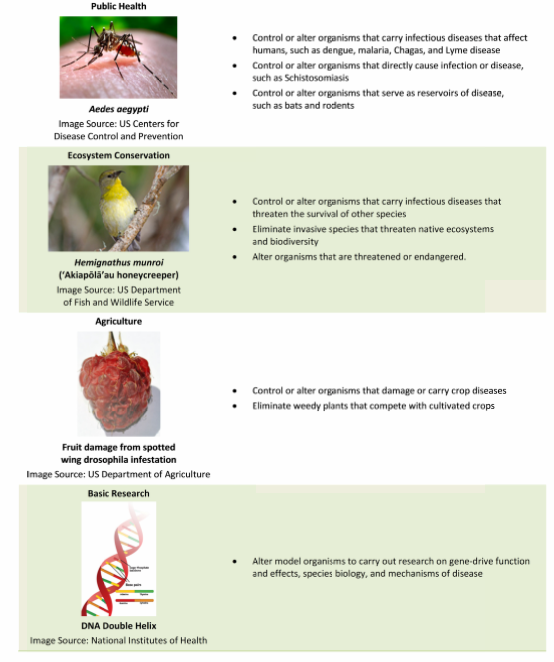

Today we have the science to edit the genome and permanently alter an insect population. By introducing new genetic traits using CRISPR/Cas9 to snip out and replace reproductive characteristics within the mosquito, breeding a sufficient number of these altered insects, and then releasing them into the wild we could eliminate a disease source. Not just Zika but Malaria, Dengue, Yellow Fever, West Nile Virus and Chikungunya, could be eliminated by destroying the mosquito source, but so could diseases like Schistomiasis and Lyme Disease by altering the genetics of the organisms that serve as disease carriers. The infographic below illustrates where and how advances in genomics can work.

The technology to do the work is known as gene drives and it comes with significant concerns. When we target a selected organism to alter it genetically we impact ecosystems in unintended ways. Back in February I wrote about ridding the world of Zika-spreading mosquitoes and potential unforeseen consequences. I pointed out that the insects themselves are not the only disease source. Once the viral load is transferred to a human host the disease can be spread through sexual transmission and blood products. At the same time if you wipe out an entire mosquito population you impact those animals that rely on the insect as a food source.

How gene drives work is well described in the video link provided here. And now the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine have recommended, in the latest 216-page report, that controlled studies begin immediately to address:

- using modified Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes to manage Dengue fever throughout the world.

- using modified Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes to combat Malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- using modified Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes to combat Avian Malaria in Hawaii.

- using modified populations of non-indigenous Mus musculus mice to protect island biodiversity throughout the world.

- using modified non-indigenous Centaurea maculosa, known as Knapweed, to protect biodiversity in forests and rangeland in the United States.

- using modified Amarantha palmeri, known commonly as Pigweed, to improve agricultural productivity in the southern United States.

To address each of these persistent species responsible for disease among humans, animal and plant populations the report proposes a “phased testing pathway” that includes risk assessment, seeks public input, provides knowledge transfer, and creates methods of oversight for regulating any introduction of gene drives into the natural environment. In its conclusions the report concludes that there is insufficient data and understanding to release gene-drive-modified organisms into the environment. It’s conclusion sums up the outstanding concerns.

“The fast-moving nature of this field is both encouraging and a point of concern. Gene-drive modified organisms hold promise for addressing persistent or difficult-to-solve challenges, such as the eradication of vector-borne diseases and the conservation of threatened and endangered species. But the presumed efficiency of gene-drive modified organisms may lead to calls for their release in perceived crisis situations before there is adequate knowledge of ecological effects, and before mitigation plans for unintended harmful consequences are in place. Continuous evaluation and assessment of the social, environmental, legal, and ethical considerations of gene drives will be needed to develop this technology responsibly and adapt research and governance to the field’s complex and emerging challenges.”

In practical terms it would seem that the Zika outbreak in Brazil presents an opportunity born of crisis where gene-drive technology could be deployed. But no one in the scientific community studying gene-drives is recommending the coming Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro to be an appropriate opportunity for a field trial. Instead more than 150 representing a dozen countries including Brazil have called for the Games to be postponed or moved. Yet the World Health Organization and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have countered this call stating that the risk is manageable. A precedent to move a major sporting event already exists. In 2003 the Women’s World Cup was moved from China to the United States because of Sars.